Tawanda Nyambirai’s recent analysis of Zimbabwe’s Constitution, published here — suggesting that Parliament could introduce a seven-year presidential term without triggering a referendum — is an intellectually stimulating and creative argument. It is also, with respect, constitutionally untenable.

By Tawonga Kurewa

Nyambirai’s passion for law is evident, and his reading of Sections 91, 95, and 328 demonstrates his enduring command of legal reasoning. However, his interpretation mistakes deliberate legal precision for ambiguity and risks normalising an approach that would erode the foundational safeguards of our constitutional democracy.

Allow me to respectfully rebut the three pillars of his argument — namely the alleged vagueness of Section 95, the notion that a new clause could be a mere “insertion” rather than an amendment, and the narrow interpretation of “term-limit provisions.”

1. The Myth of Ambiguity in Section 95

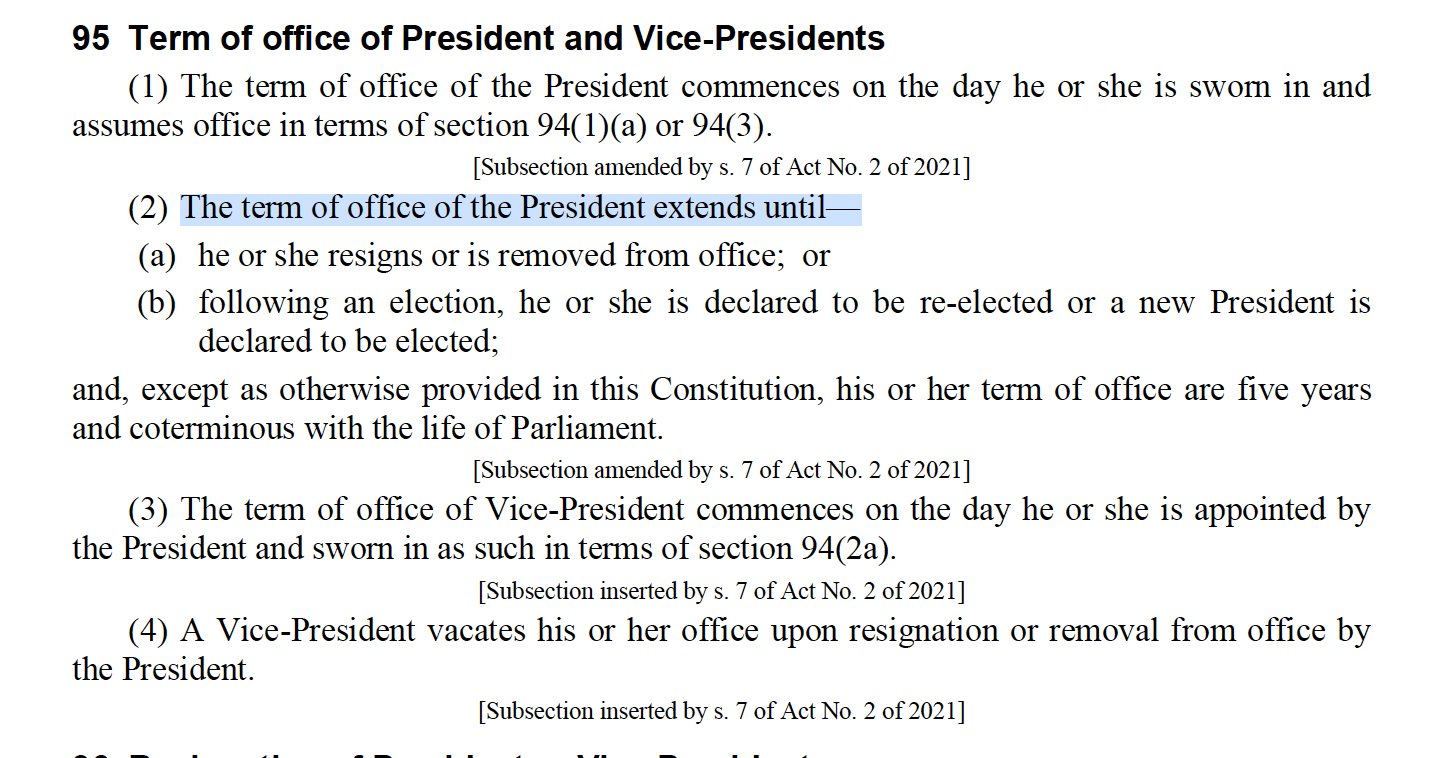

Nyambirai contends that the drafters of the Constitution were uncertain about the duration of a presidential term, citing the phrasing in Section 95(2): “… except as otherwise provided in this Constitution, their terms of office are five years and coterminous with the life of Parliament.”

He suggests that the phrase “except as otherwise provided” leaves open the possibility of another provision being introduced later to set a different duration, such as seven or ten years.

That reading, however, misunderstands a well-established drafting convention. This phrase does not signal indecision, nor does it create a constitutional gap. It is a harmonising clause, ensuring internal consistency among interconnected provisions of the same legal instrument.

For instance, Section 94(2) ensures continuity of executive authority until the assumption of office by the President-elect, while Section 158(1)(a) regulates the timing of elections so that polling occurs within thirty days before the expiry of the five-year period. These provisions do not dilute or contradict the five-year term — they merely regulate its practical operation.

In other words, the drafters were not unsure. They were precise. The five-year term is clear and definitive. The qualifying phrase was inserted not to invite speculative reinterpretation but to ensure the Constitution functions coherently as a whole.

2. An “Insertion” Is Still an Amendment

Nyambirai’s central thesis is that Parliament could “insert” a new clause providing for a seven-year term without amending Section 95. But in constitutional law, form cannot disguise substance.

An insertion that alters the legal effect of an existing provision is, by definition, an amendment. The idea that one can modify the duration of a presidential term by simply adding a new provision — without formally amending the section that already prescribes a five-year term — is logically and legally unsustainable.

If a new clause were to declare, “A presidential term shall be seven years,” it would not merely fill a gap; it would directly contradict the current five-year term. The effect would be to repeal and replace the existing rule. Such a move cannot be disguised as a technical “insertion” — it would be a full-blown constitutional amendment, subject to the stringent procedures of Section 328.

3. Term Limits Include Duration as Well as Number of Terms

Nyambirai attempts to draw a distinction between the number of terms (addressed in Section 91) and the length of each term (addressed in Section 95), arguing that changing the latter does not amount to altering a “term-limit provision.”

That interpretation, though creative, is far too narrow. The concept of a term-limit provision encompasses any clause that constrains how long a person may hold presidential office — whether by limiting the number of terms or the duration of each term.

Therefore, Sections 91 and 95 together form an integrated framework of presidential tenure. Any attempt to extend the term duration would, without question, amount to amending a term-limit provision.

Section 328(7) was specifically crafted to prevent exactly this kind of manoeuvre. It states unequivocally that: “An amendment to a term-limit provision does not apply in relation to any person who held or occupied that office at any time before the amendment.”

This clause was inserted as a constitutional firewall against self-serving amendments — ensuring that no incumbent can benefit from their own term extension.

Even if Parliament, by the requisite majority, were to pass a constitutional bill extending the term to seven years, Section 328(7) would render that amendment prospective only. President Mnangagwa, or any sitting President, could not lawfully benefit from it.

4. The Framers Left No Lacuna — They Built Safeguards

Contrary to Nyambirai’s suggestion, the framers of the 2013 Constitution did not leave a “gap” or “lacuna.” They built a layered system of protections precisely to prevent the political manipulation of executive tenure.

The five-year presidential term, the two-term cap, and the referendum requirement for amending entrenched provisions together form a deliberate architecture of restraint. To reinterpret these clauses as open invitations for extension is to dismantle the very ethos of constitutionalism — that power must be limited, and that the rules cannot be rewritten by those who stand to benefit.

Conclusion

Tawanda Nyambirai’s analysis is intellectually stimulating, but it collapses under the weight of constitutional coherence. The five-year presidential term is neither vague nor optional. The phrase “except as otherwise provided” is not a licence for political creativity but a mechanism for internal consistency.

Any attempt to introduce a seven-year term — whether by amendment or so-called insertion — would constitute an alteration of a term-limit provision. As such, it would trigger Section 328(7) and the referendum requirement.

The Constitution, therefore, does not permit the incumbent to benefit from a self-engineered extension. The drafters anticipated precisely this temptation — and closed that door firmly.

To insist otherwise is not a defence of constitutional interpretation; it is an invitation to constitutional subversion.

The author, Tawonga Kurewa, is a constitutional law analyst and legal commentator. The views expressed are his own.