EXPLAINER: Objectively Zanu PF’s 2024 Resolution Number 1 Would not Require a Repeal of the Presidential Term Limit Provision or a Referendum.

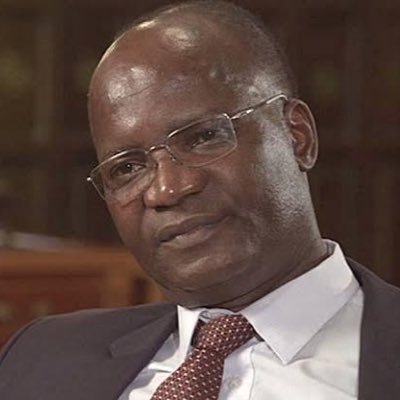

By Prof. Jonathan Moyo

INCREASINGLY across Zimbabwe’s political spectrum, there’s a proliferation of unsubstantiated claims that the governing Zanu PF party is plotting to excise the presidential term limit from the 2013 Constitution, ostensibly to grant President Emmerson Mnangagwa a third term or stretch his current one—set to expire in 2028—through to 2030. These assertions, devoid of concrete evidence, have ebbed and flowed since around September 2024, intensifying ahead of the Zanu PF People’s Conference in Bulawayo that October, where a resolution urged extending Mnangagwa’s presidency beyond 2028 to 2030. Now, with the party’s 2025 conference looming in Mutare, Manicaland, on 13 October, the “2030 mirage” has reignited once again, recycling the same uninformed and misinforming narratives that Zanu PF aims to dismantle the presidential term limit provision.

Make no mistake: If Zanu PF is in fact entertaining the repeal of the presidential term limit by hook or crook, that would undoubtedly represent a profound threat to Zimbabwe’s democratic framework—even if executed in accordance with the rigorous amendment process in section 328 of the Constitution. The repeal would demand a Constitutional Bill securing two-thirds affirmative votes from each House of Parliament, followed by approval in two separate national referendums. Why? Because presidential term limits stand as one of the essential pillars of any democratic constitution—as a bulwark against authoritarian entrenchment.

Without term limits on key officials of the State, the very notion of a democratic constitution crumbles.

Yet, amid the resurgence of alarmist narratives tying the “2030 agenda” to term limit repeals, a critical question demands scrutiny: Is this in fact what is conveyed by Zanu PF’s October 2024 resolution of the party’s National People’s Conference, whose content is in the public domain?

The term “term-limit provision” is no vague slogan or political weapon; it is a precise legal concept defined explicitly in section 328(1) of the Constitution, which governs the making of constitutional amendments: (1) In this section—

“term-limit provision” means a provision of this Constitution which limits the length of time that a person may hold or occupy a public office.

In essence, a term-limit provision imposes a fixed, quantifiable cap on an individual’s tenure in office—a numerical limit or cumulative duration with a clear start and an unequivocal, determinable end, beyond which continued occupancy becomes unlawful.

Crucially, such provisions emphasize maximum tenure, often phrased with ironclad finality: “non-renewable term of X years,” “X-year term renewable only once,” or “not more than two terms, whether consecutive or not, where a minimum of X years shall count as a full term.”

Zimbabwe’s Constitution contains approximately 15 such ironclad term-limit provisions, all sharing this genus without exception. Any clause lacking these hallmarks simply is not a term limit provision.

Applied to the presidency, the authentic term-limit provision resides in section 91(2):

A person is disqualified for election as President or appointment as Vice-President if he or she has already held office as President under this Constitution for two terms, whether continuous or not, and for the purpose of this subsection three or more years’ service is deemed to be a full term.

This provision is the bedrock safeguard, amendable under section 328(5) with two-thirds parliamentary approval and the dual referendums per subsections (7) and (9). Two vital truths emerge here.

First, repealing section 91(2) would indeed be catastrophic for constitutional integrity. Second—and decisively—there is zero evidence, from the dawn of the 2030 discourse to now, that Zanu PF has any proposal, resolution, or intent to tamper with section 91(2).

None at all.

So, whence this frenzy over alleged term-limit violations, and how much of it transcends mere political opportunism? It’s undisputed that neither Zanu PF nor the government has introduced a Bill advancing the “2030 agenda.” The sole public record is Resolution 1 from the October 2024 Zanu PF People’s Conference in Bulawayo, which urges that:

“The President and First Secretary of ZANU PF Party, His Excellency, Cde. Dr. E.D Mnangagwa’s term of office as President of the Republic of Zimbabwe and First Secretary of ZANU PF be extended beyond 2028 to 2030. The Party and Government should, therefore, set in motion the necessary amendments to the National Constitution so as to give effect to this resolution.”

This resolution neither mentions nor implies repealing the presidential term limit in section 91(2). Instead, it targets a singular focus in dual dimensions: extending Mnangagwa’s current term of office—as President of Zimbabwe, and as Zanu PF’s First Secretary.

For his role as “President of the Republic of Zimbabwe,” the pertinent constitutional clause is section 95(2)(b), which outlines the term of office (not limit):

(2) The term of office of the President extends until—

(a) ………….

(b) following an election, he or she is declared to be re-elected or a new President is declared to be elected; and, except as otherwise provided in this Constitution, his or her term of office is five years and coterminous with the life of Parliament.

Evidently, the 2024 resolution eyes an amendment to section 95(2)(b)—although no such draft has so far materialised from Zanu PF or the government. Under section 328(5), this would require only a Constitutional Bill passing both the National Assembly and Senate with two-thirds majorities in each. No referendum is required because, contrary to the clamour, section 95(2)(b) is not a term-limit provision.

It imposes no cap on total terms or cumulative service; it merely delineates each term’s duration—five years, aligned with Parliament’s lifespan—without the definitional finality of a term limit as per section 328(1).

Moreover, unlike true term limits with clear start-points and fixed endpoints, section 95(2)(b) accommodates variable starts (e.g., via election, appointment after a vacancy) and conditional ends (e.g., resignation, impeachment). Its coterminosity with Parliament—itself prone to dissolution on multiple grounds—introduces inherent variability, amplified by the clause “except as otherwise provided in this Constitution.”

Thus, amending section 95(2)(b) would align squarely with section 328(5), without a referendum.

To reiterate: The actual presidential term limit, demanding referendum-backed amendment, is section 91(2). Zanu PF’s resolution skirts it entirely.

As an aside, those same voices erroneously labelling section 95(2)(b) a term limit provision—insisting its amendment requires a referendum—have extended their fallacy to section 143(1), on Parliament’s “Duration and dissolution,” which provides that:

(1) Parliament is elected for a five-year term which runs from the date on which the President-elect is sworn in and assumes office in terms of section 94(1)(a), and Parliament stands dissolved at midnight on the day before the first polling day in the next general election called in terms of section 144.

Recall that section 328(1) defines term limits solely for persons holding public office.

Section 143(1) governs the institution of Parliament—not individual parliamentarians. It sets out structural cycles for the legislative body (comprising the National Assembly and Senate), framing each “Parliament” as a five-year entity. Per Standing Order 44, a “session” spans one year; Standing Order 46 mandates five sessions (or years) per Parliament, starting post-general election with the President’s State of the Nation address. Zimbabwe’s first Parliament convened in 1980; today, we have the Tenth.

This institutional timeline imposes no cap on the personal tenure of MPs—governed by section 129 of the Constitution, read with sections 121, and 125; which allow for indefinite re-election of MPs.

It must be said emphatically, that this approach mirrors the overwhelming global consensus: Out of 193 United Nations member states, only about 11—virtually all from Latin America, such as Bolivia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, and Mexico—impose term limits on legislators.

This means a staggering 182 countries, including Zimbabwe, reject such legislative constraints, as term limits on parliamentarians are almost unheard of and decidedly not the norm in constitutional democracies worldwide. Hence, section 143(1) is patently not a term-limit provision under section 328(1). Its amendment demands only two-thirds parliamentary approval under section 328(5), with no referendum required.

In sum, the 2030 narrative is riddled with misinformation, conflating term of office clauses with term-limit provisions. The public deserves clarity to enable it to make informed choices: Safeguarding the Constitution means confronting facts, not fuelling phantoms.

If Zanu PF proposes an amendment to the Constitution, which it has done through the party’s October 2024 Resolution Number 1, let that proposal be debated on its merits—unclouded by hysteria based on uninformed and misinforming claims.