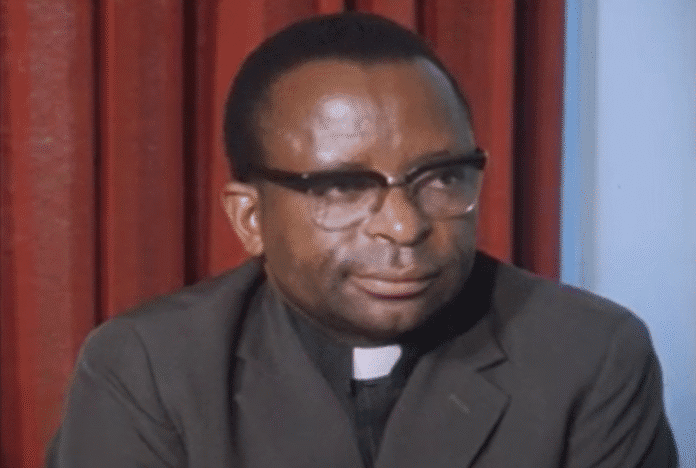

In September 1978, Mozambique’s first president, Samora Moisés Machel, delivered a speech in Maputo that dissected the mechanics of imperialist strategy in Southern Africa. He argued that Britain, the United States and their allies had no intention of dismantling settler colonialism or apartheid at their roots. Their goal, he said, was to preserve the structures of economic exploitation, disguised under new leadership acceptable to international opinion.

By Solo Musaigwa

Machel was blunt. The true target of imperialism was not Ian Smith’s Rhodesian regime, nor South Africa’s apartheid rulers, but the liberation movements themselves. These, he believed, carried the potential to radically transform power relations. For that reason, they had to be neutralised, divided or redirected. Independence might eventually come, but only on terms that safeguarded foreign interests.

The dual strategy

According to Machel, imperialism operated with two parallel strategies. One was the “internal solution”: grooming local collaborators, from Abel Muzorewa to Ndabaningi Sithole, who could be presented as national leaders while leaving colonial structures intact. The other was the “international solution”: high-profile conferences, Anglo-American plans, and promises of peaceful transition, which allowed external powers to retain control over the timetable and the outcome.

Whenever one path faltered, the other was revived. If armed struggle intensified, international diplomacy was activated to defuse it. If negotiations stalled, internal settlements were promoted as pragmatic compromises. The cycle ensured that while political independence might be conceded, the deeper economic architecture of privilege remained untouched.

The historical pattern

The liberation of Zimbabwe in 1980 illustrates the dynamic. After years of brutal conflict, the new state emerged with its political sovereignty recognised, but still tethered to patterns of international finance and trade that limited genuine self-determination. Settler-derived interests were protected under the Lancaster House arrangements, ensuring that the structures of ownership changed slowly, if at all.

South Africa’s transition in 1994 followed a similar trajectory. Apartheid rule ended, but the commanding heights of the economy land, capital, and mineral wealth remained concentrated. Namibia’s path to independence also carried the fingerprints of compromise, designed to calm international fears of radical transformation.

The outcome across the region was consistent: freedom celebrated, yet constrained by conditions that preserved dependency. Machel’s prediction that imperialism would adapt rather than retreat proved prescient.

Continuities today

The same logic is visible today, though in subtler forms. The language of imperialism has shifted from “settlement” and “transition” to “partnership” and “development.” The instruments are no longer colonial governors or Rhodesian settlers but international lenders, aid agencies and investors.

Debt diplomacy has become a powerful lever, binding states to repayment schedules that limit policy autonomy. Aid packages come with conditions that prioritise market liberalisation and fiscal restraint over structural transformation. Appeals to “investor confidence” keep governments in check, ensuring that radical economic policies are either delayed or abandoned.

The result is a paradox: African states are politically independent, but economically constrained. Sovereignty is celebrated at the level of flag and anthem, yet diluted in practice by an enduring reliance on external approval and resources.

The unfinished question

Machel’s central question remains unanswered: is independence meaningful without economic sovereignty? For him, liberation was never about symbols alone. It required dismantling systems of privilege, reclaiming resources, and empowering people to shape their own futures. A seat at the United Nations or a change of flag did not equal emancipation if the structures of exploitation persisted.

Nearly five decades later, this challenge is as pressing as ever. Zimbabwe’s liberation struggle came at immense human cost. The massacres at Nyadzonia, Chimoio and Tembwe are remembered as testimony to the sacrifices made. Yet if the struggle’s economic goals are not pursued with equal determination, the risk is that independence becomes an unfinished project politically achieved but economically compromised.

The enduring warning

Imperialism, Machel insisted, is not a relic but a shapeshifter. It adapts, reinvents and disguises itself. It no longer arrives in settler uniforms but in tailored suits and investment portfolios. It does not speak of racial supremacy, but of partnership, stability and assistance. Yet the results dispossession, dependency and division remain alarmingly similar.

This is why his warning remains urgent. The greatest danger lies not in overt domination, which can be resisted openly, but in solutions presented as benevolent while preserving inequality. Independence, he reminded us, is not a gift to be granted by London, Washington or Pretoria. It is a process of constant struggle, requiring vigilance against compromises that entrench dependency.

Towards genuine sovereignty

For Zimbabwe and Southern Africa, the unfinished business of liberation lies in bridging the gap between political sovereignty and economic freedom. This means revisiting fundamental questions of land, ownership, trade and resource control. It also means building regional solidarity to resist the pressures of external actors who continue to shape outcomes in their own interests.

Machel ended his 1978 speech with a declaration of faith: Zimbabwe will be independent, the people will win, Africa will triumph. His words carried both hope and warning. Hope that liberation could be achieved, and warning that it would be undermined if exploitation was allowed to persist under new names.

Nearly half a century on, the responsibility to act on that warning rests not with foreign capitals but with Africa itself. The unfinished business of independence is not merely to recall the sacrifices of the past but to complete their promise transforming political freedom into genuine sovereignty.